Panic attacks are one of the most frightening things that can happen to us, especially when we consider ourselves rational and intelligent human beings that are typically in control of our lives.

The first time or even the first few times we experience panic attacks, we feel like we are dying while our brain scrambles to make sense out of something that makes no sense at all.

Understanding what happens in our brain and our bodies during panic attacks is a critical step in gently accommodating ourselves while we learn the skills to share a life with panic disorder.

It starts with the brain

Since the brain is the control center for everything that happens in our bodies, it makes sense that this is also the focus for panic disorders.

The good news is that over the last few decades, scientists have unlocked new truths about what happens in our brain during panic attacks. This leads to research and treatments that can help people decrease the frequency and intensity of these attacks.

The bad news is, there is still so much that we do not know. We are learning that there are many more parts of the brain involved than first thought and genetics play a factor as well.

The amygdala

The amygdala is still believed to be the primary player in panic attacks. The amygdala is the part of our brain responsible for our fight-or-flight response and some emotional regulation.

A well-functioning amygdala has kept us alive as a species. It stores memories of things that are harmful to help us avoid them in the future. It is the very response that has helped us develop survival skills that sets us up for susceptibility to panic attacks.

Recent research shows that the initial fear or panic may be generated in another part of the brain signaling the amygdala to respond to danger. Depending on a number of different conditions, the amygdala may react in an extreme manner bringing on a panic attack.

The other players

The amygdala signals its brain partners to release chemicals to help our bodies respond to perceived danger. What ensues is a cycle of signals across the brain, both chemical and physical that unleash a cascade that make us susceptible to panic attacks.

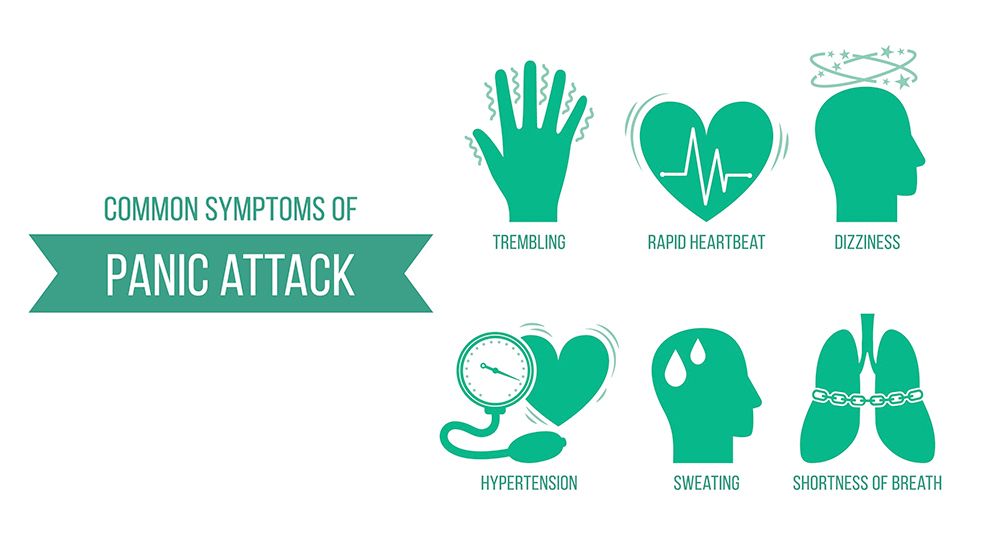

It is believed that the locus coeruleus, located in the brain stem, is triggered by sending nerve signals that increase heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar.

Simultaneously, it is believed that the adrenal glands – located on the top of each kidney – release epinephrine and norepinephrine further stimulating the body’s stress response; pupils dilate, digestion slows, and heart and breathing rate increase, preparing our bodies for survival.

What happens next?

As our breathing quickens, we start to hyperventilate. This causes our body to retain more carbon dioxide (CO2) resulting in feelings of light-headedness and confusion.

The thinking part of our brain that is still working – barely – begins questioning if we are having a heart attack, if we are getting enough oxygen, and if we are going to live through this.

All of these changes can occur very quickly and are the biological basis for panic attacks. It is important to understand that this is very often out of our control.

Out of our control

Many of us are probably thinking right now, but I have learned to control my panic attacks. This can happen in some situations.

We can use various techniques to recognize the onset of our anxiety and panic triggers to decrease the prevalence and severity of panic attacks. Medications can also be effective for some people in slowing down the panic process in our brains.

But we cannot fully control the above physiological response once it has started. This is deeply rooted in our survival.

Understanding this goes a long way in helping us see that we are not going crazy and there is not something wrong with us. Our responses are just a bit out of balance.

What do we do with this information?

The same techniques that help us manage stress and anxiety can help us decrease the frequency and intensity of panic attacks. Cognitive-behavioral therapy or CBT can help us learn to practice with small anxiety triggers to train ourselves and our brain to begin to slow down the panic process.

Remember that our amygdala contributes to the memory of dangerous situations and speeds up our responses. We can consciously plant new memories in our amygdala about things we previously perceived as dangerous to override the panic response.

We all experience anxiety and panic attacks differently. Working closely with a mental health professional can help us deepen our understanding of the brain’s processes and how we can influence them. Living life with anxiety and panic disorders is possible with the right tools and support.